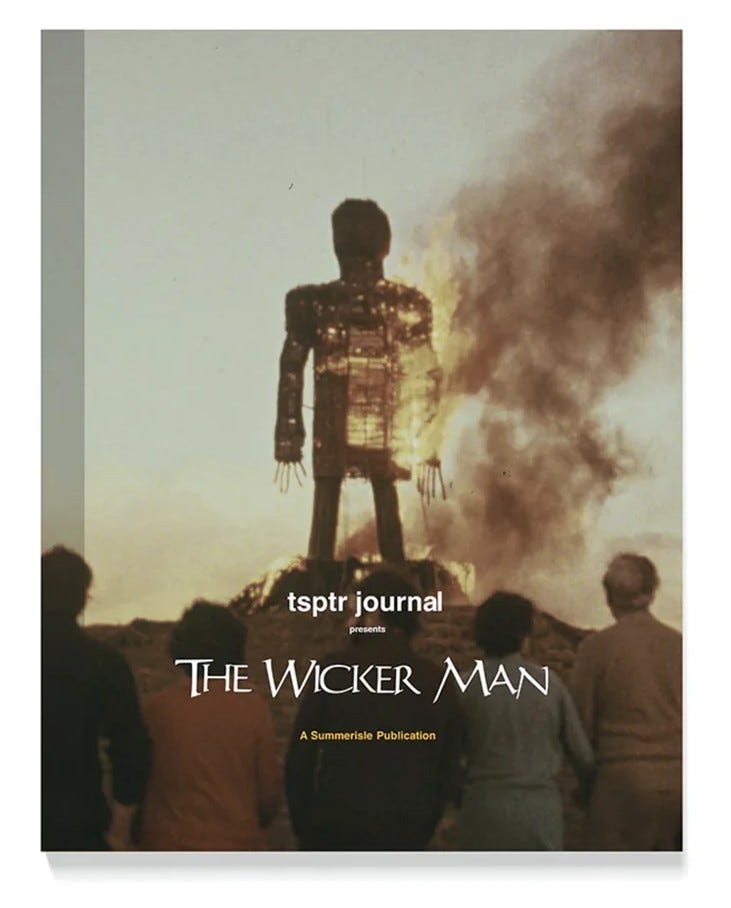

A long out-of-print Weird Walk article from TSPTR’s 2023 Wicker Man journal is presented here for your reading pleasure…

“What my grandfather had started out of expediency, my father continued out of love. He brought me up the same way, to reverence the music and the drama and the rituals of the old gods. To love nature and to fear it, and to rely on it and to appease it where necessary.”

Lord Summerisle, The Wicker Man

The Wicker Man is the most iconic of folk horror films – if there is one entry in the canon of this loosely woven genre that reaches out from cultish hinterlands into game show answers, popular music and even fashion, this is the one. It is also a truly brilliant British film, and more diverse than many in the category it was retrospectively fitted-up to signify. Within its infamously edited and reconfigured reels we find musical theatre, seventies police drama and bizarre ritual performance before a final moment of terror. And, of course, it’s a great story.

Key to the film’s impact, and its continued appeal, is the vibrant grab bag of folkloric motifs assembled by director Robin Hardy and writer Anthony Shaffer. Summerisle’s culture is full of references to traditional customs, sympathetic magic and literary accounts of pagan practices. One source, however, influenced The Wicker Man more than any other. The Scottish anthropologist Sir James Frazer’s sprawling multi-volume work, The Golden Bough, is the movie’s Rosetta Stone. In fact, The Golden Bough (subtitled A Study in Magic and Religion) contains ideas that vibrate strongly within the world of what has come to be known as folk horror as a whole, ideas that escaped from Victorian academia and were reshaped by writers, poets and filmmakers, before they became part of contemporary folklore itself.

The core of Frazer’s thinking runs something like this: humanity was once ruled by sacred kings who symbolised a vegetation god that ensured a bountiful harvest. At a particular time, and to guarantee continued abundance, the king was killed and replaced – the death and rebirth of the land ritually enacted. Echoes of this stage of human development can be heard across the world, and, if we look closely enough at our ancient traditions, buildings, stories and songs, we will discern traces of its presence. Perhaps, we might speculate, the sacrificial practices of the ancestors are still observed in more remote corners, threatening the order of modernity and reinforcing a primal connection to the soil.

Frazer’s chief aim in his text (which had grown to a wheelbarrow-load of twelve volumes by 1915) was to demonstrate that all societies move through different stages of cultural evolution: magic, religion and, finally, science. As an arch-rationalist, he considered the final stage of this evolution to be the most elevated position for humanity. It is only at the initial, magical stage that we find our fertility cult with its sacrificial kings. The first edition of The Golden Bough caused uproar by suggesting that Christ was merely a religious iteration of one of these sacred kings: a dying and rising god who emerged from a remnant memory of ancient rites. Frazer presented a remarkable array of material in his tomes, and made some fantastical leaps to draw it towards his themes. If he wasn’t keen on Christianity, he was even less of a fan of paganism, which he largely considered a form of savage superstition. The historian Ronald Hutton has pointed out that this view wasn’t born only of Frazer’s rationalism, but also an outlook that was markedly colonial and elitist even by the standards of the time.[1]

Frazer’s ideas were initially received enthusiastically by academics, but by his death in 1941, the flaws in his theories had long been revealed, and professional historians and anthropologists had moved on. The evidence for Frazer’s ancient universal vegetation cult simply didn’t stack up. His work, however, would take on a new life outside scholarly investigation. Inverse to its rejection by the academy, there was an embrace of The Golden Bough in fictional worlds, where a poetic interpretation of the fertility religion was reformulated into myriad weird and wonderful constructions, often by artists with radically different views to Frazer’s own.

For Hardy and Shaffer, the Bough was a treasure trove. Many of the pagan details included in The Wicker Man originated with Frazer, before being given a uniquely Summerisle twist. The fire leap, one of the film’s most famous scenes, certainly draws upon the Scot’s work. Sergeant Howie, on his way to Summerisle Castle, witnesses a group of girls leaping naked through flames within a stone circle “in the hope that the god of the fire will make them fruitful”. The puritanical Howie is, of course, aghast and complains about the nudity to Lord Summerisle, who retorts that it would be far too dangerous to jump through fire with your clothes on. Frazer makes many links between fertility and fire, pointing out myths which include phallic flames and legendary kings conceived by sparks. He goes on to note that when sacred fires were kindled, this may have been through the rapid turning of a holed stick and a drill stick, and that here it is possible to see “a resemblance to the union of the sexes”.

Elsewhere, we see the planting of trees on graves referenced by Frazer as a Chinese custom, much like Rowan Morrison has a rowan tree planted on her (supposed) resting place. The hanging of a “navel string” upon the tree is drawn from Frazer, as is the idea that grave earth will give you a good night’s sleep, but the hand of glory will knock you right out. Other touches, such as the frog-in-the-mouth sore throat cure and the beetle on a string in Rowan’s school desk, can also be found among the many pages of the Bough.

Frazer addresses the imposing figure of the wicker man itself as a custom of the Druids. In an early edition of The Golden Bough he agrees with the German folklorist Wilhelm Mannhardt’s interpretation of its purpose: “He supposed that the men whom the Druids burned in wicker-work images represented the spirits of vegetation, and accordingly that the custom of burning them was a magical ceremony intended to secure the necessary sunshine for the crops.” In later editions, however, Frazer isn’t so sure. Rather than a fertility ceremony, the anthropologist proposes that the wicker man allowed the community to ritually execute “noxious and dangerous beings”, such as those guilty of witchcraft. It has been suggested that Hardy and Shaffer worked from an early, Victorian edition of the Bough, but regardless, Mannhardt’s theory is a much better fit for the film.

The May Day celebrations that precede Howie’s sacrifice also have a Frazerian tone. The Wicker Man has perhaps fixed in the mind the idea of the maypole as, in the words of Miss Rose and her students, a phallic symbol: “it is the image of the penis, which is venerated in religions such as ours as symbolising the generative force in nature.” Frazer makes several references to maypoles, linking them more to tree worship than sexual symbolism, and although contemporary folklorists will tell you there is zero evidence for either theory, it’s easy to see why maypoles were a neat addition to Summerisle’s paganism.

Alongside the climactic inferno and Willow MacGregor’s naked dance moves, the film’s May Day procession provides some of its most recognisable visuals. Here, a wonderful collection of characters, based largely on British traditions, can be seen in action. As Katherine Wetherell points out in her blog cross-referencing The Wicker Man with Frazer’s work, Lord Summerisle’s famous exhortation to Punch/Howie to “cut some capers, man!” is directly sourced from Frazer.[2] The Golden Bough mentions the Padstow ‘Obby ‘Oss and various mummers, regarding leafy performers such as the Jack-in-the-Green as representative of the vegetation spirit. Although we now know that the likes of the Jack were established more recently than was once thought, for Frazer, these processions, plays and dances were an echo of the magical stage of human evolution. He also noted their waning potency in his own time: “no longer regarded as solemn rites on the punctual performance of which the welfare and even the life of the community depend, they sink gradually to the level of simple pageants, mummeries, and pastimes”. In keeping with his dim view of such customs, he reassured his reader not to worry about their disappearance, for “our regret will be lessened when we remember that these pretty pageants, these now innocent diversions, had their origin in ignorance and superstition”.

Perhaps here, we get to one of the most interesting tensions in both The Wicker Man and The Golden Bough. Frazer intended his graphic descriptions of pagan ritual and custom to confirm the superiority of the scientific worldview in his readers’ minds. For many, however, the text did exactly the opposite, awakening a yearning for a lost, magical world and nudging them to seek out the relics of earlier times that can still be found in folklore and legend.

The shock of industrialisation was still raw during Frazer’s lifetime, and a connection to nature, place and tradition was very much in the process of being broken. In 1917, the German sociologist Max Weber gave a lecture which introduced his signature phrase: “The fate of our times is characterised by rationalisation and intellectualisation and, above all, by the Entzauberung der Welt.” One translation is simply ‘the unmagicking of the world’.[3] The Golden Bough arrived in an era of quite literal disenchantment, and some writers would soon take the text’s enormous suite of materials, and rewire its purpose to allow a little of that magic back. T. S. Eliot, Robert Graves, James Joyce and H. P. Lovecraft all drank from its vast well of inspiration. In common with the reception to The Golden Bough’s paganism, many of us can’t help but be drawn to the free-spirited islanders, who stand in such sharp contrast to Howie’s buttoned-down religiosity. It is only at the last that we are forced to question where our loyalties really lie.

Of course, having The Golden Bough as the main source of information for the pick ‘n’ mix of folk practice represented so captivatingly in The Wicker Man has led to plenty of irritation in some quarters, with one commentator describing the film’s effect as one of “a folkloric amusement park”.[4] However, in spite of the tongue-in-cheek thanks given to Lord Summerisle in the opening titles, it is doubtful that anyone has approached the movie as a documentary. As Adam Scovell points out in his overview of the genre, “It is worth noting how critical folkloristic scholars can be towards the more overt folk horror material, perhaps because it enjoys such open freedoms with the history that they take great pains to contextualise, and it plays mischievously with various (heavily mythologised) interpretations for the sheer hell of it.”[5]

Interestingly, despite Hardy and Shaffer’s apparent face value take on The Golden Bough’s veracity, there is a viewer-led interpretation of The Wicker Man that could potentially please even hardened members of the authenticity police. One point that critics of the film’s apparent appropriation of various folkloric moves can miss is that Summerisle’s practices are a revival rather than a survival. Lord Summerisle is clear that paganism was introduced to the Christian people of the island by his grandfather as part of a scheme to win their loyalty and labour. Isn’t the resulting culture exactly the kind of concoction “a distinguished Victorian scientist” might implement as a vision of a pagan society? His Lordship gives the date of the purchase of the island as 1868, a little early to have read The Golden Bough (which was first published in 1890) in our speculative Wickerverse, but with plenty of time to become familiar with the work of Wilhelm Mannhardt, Jacob Grimm and others. Perhaps Summerisle’s beliefs are exactly what the old boy intended.

Needless to say, The Golden Bough’s cinematic vines tangle far further than one movie. Following on from early adopters in the literary world, film and TV soon caught up with the potential of a dormant vegetation cult along Frazerian lines. The BBC’s haunting 1970 Play for Today entry ‘Robin Redbreast’ is explicitly indebted to the Bough, weaving the notion of deadly fertility rites into its tale of town and country colliding. Earlier still, 1966’s Eye of the Devil explored harvest sacrifice in a rural French setting. More recent examples include a brilliantly dark episode of Inside No. 9 entitled ‘Mr King’, the harrowing Kill List and the sinister rituals of Midsommar. Ari Aster, Midsommar’s writer-director, followed in Hardy and Shaffer’s footsteps with his earnest use of the Bough as research for pre-Christian belief. Any guffaws from the academy again miss the point here, as Frazer’s compendium would have provided the perfect springboard for Aster’s fictions. The Bough still offers fuel for strange fires.

The final layer of The Golden Bough’s onion of influence is perhaps the weirdest and most hauntological. In some cases, the very customs that Frazer referenced have now accrued his theories as part of their origin stories. Refracted through the lens of artistic interpretation and popular culture, fertility rites have, at various points, been linked to everything from morris dancing to cheese rolling, with local newspaper coverage of British traditions having a particularly Frazerian leaning. A quick Google reveals that many old customs are haunted by a history that never was.

Where does all of this leave our beloved film and its relationship with paganism and folklore? The Wicker Man has certainly raised the profile of a once obscure element within classical accounts of Druidic rites. Wicker giants can now be found burning at festivals and re-enactments across the globe, from the Beltane celebrations at Hampshire’s Butser Ancient Farm to Burning Man in the Nevada desert. It is possible that more wicker men have been burned since 1972 than during the entire Iron Age. In her excellent history of paganism, the writer Liz Williams notes that although there are issues with its portrayal on screen, people’s initial interest in paganism as it is practised today is often kindled through exposure via TV and film. In the case of The Wicker Man, the pull of the islanders’ liberal attitudes and ritual connection to the natural world is a strong one. Williams also states that contemporary paganism’s real power lies in its ability to deal with the everyday rather than the sensational and extraordinary: “It is not about what you wear and how impressive you look at the end of the day, but whether, for example, it can help you through a night in intensive care when your loved one is dying, or inspires you to go out and plant a tree on a ravaged industrial estate…”[6]

In the world of folklore, The Golden Bough still casts a long shadow, although these days it is itself a source for the interrogation of a particular Victorian worldview. Now far removed from its author’s original intentions, it also remains (especially in its unabridged form) a vast compendium of fascinating material. After many years where small, local studies were the norm, anthropologists are even reviving a global, comparative approach to their subject, albeit shorn of the colonial trappings of Frazer’s work.[7] And although there may be no evidence for a Wicker-like ancient fertility cult, there are certainly pagan echoes on these islands if we choose to look in the right places. These range from the specific, such as the scouring of the Uffington White Horse, to broader cultural relics that pre-date Christianity, such as the giving of gifts at midwinter or the ritual lighting of fires. The wheel of the year has always turned, and people have always acknowledged its key moments. The forms may be more modern than once thought, but the impulses are undeniably ancient. And if The Golden Bough’s influence is now largely confined to fiction, the desire to reconnect with our enchanted land, with its traditions and lore, is as real as ever.

[1] Hutton, R. (2022). Queens of the wild: pagan goddesses in Christian Europe: an investigation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

[2] Wetherell, K. (2020). How The Golden Bough inspired The Wicker Man. [online] Ye Olde Witchcraft Shoppe. Available at: yeoldewitchcraftshoppe.co.uk

[3] Crawford, J. (2020). The trouble with re-enchantment. [online] Los Angeles Review of Books. Available at: lareviewofbooks.org

[4] Koven, M. J. (2007). The folklore fallacy: a folkloristic/filmic perspective on The Wicker Man. Fabula, 48 (3-4)

[5] Scovell, A. (2017). Folk horror: hours dreadful and things strange. Leighton Buzzard: Auteur Publishing.

[6] Williams, L. (2020). Miracles of our own making: a history of paganism. London: Reaktion Books.

[7] Hutton, R. (2022). Queens of the wild: pagan goddesses in Christian Europe: an investigation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Great article.

This was absolutely wonderful to read.