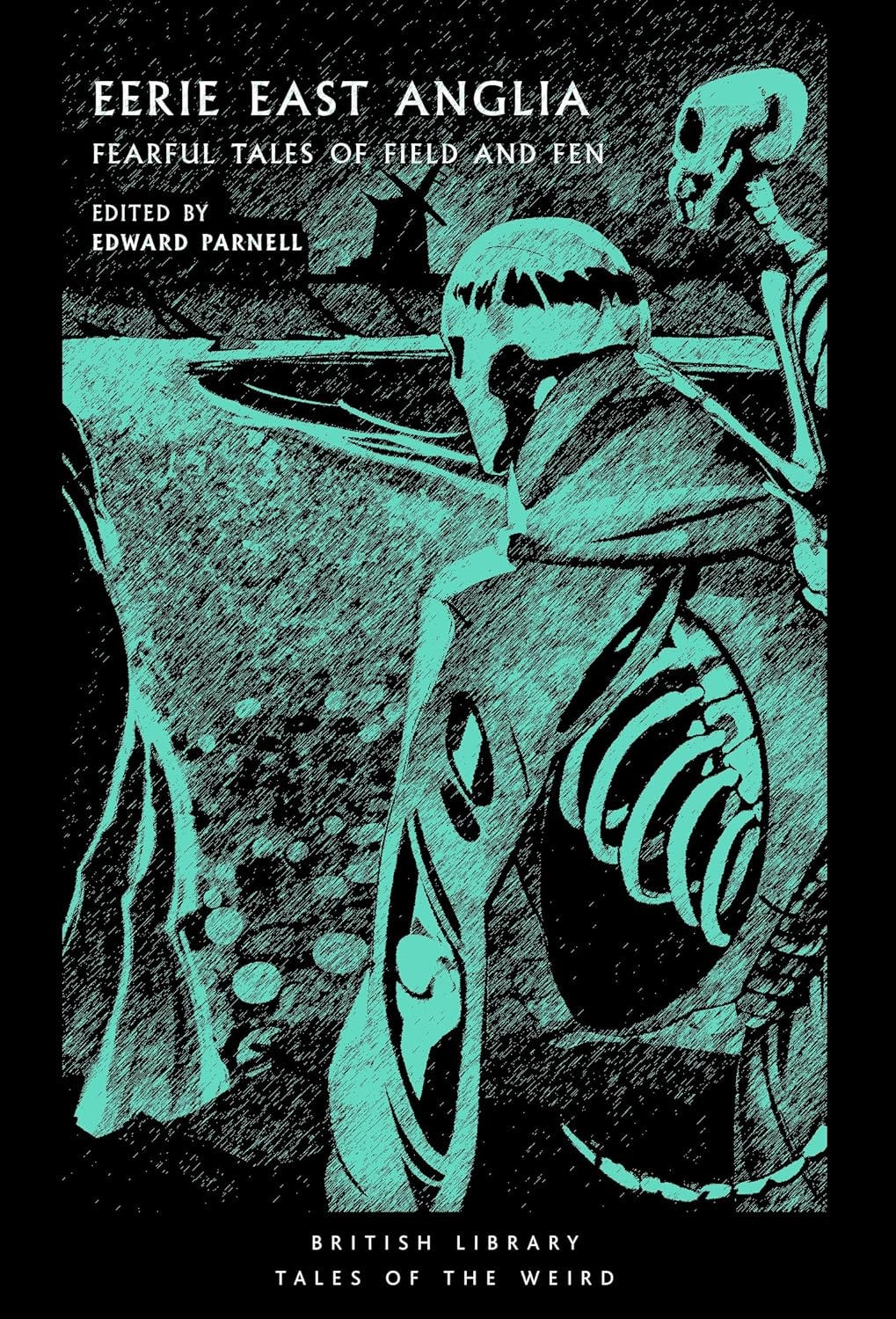

With our own addition to the British Library’s Tales of the Weird strand dropping on 19 September, we have been catching up on some other books in the series, and we were particularly taken by Edward Parnell’s selections in Eerie East Anglia, which is available now in the Weird Walk shop.

We talked to Edward about this loosely defined area, one of our favourite parts of Britain, and the uncanny fiction it has inspired.

East Anglia is a great subject for a collection of weird tales. Why do you think this landscape has accrued so many literary hauntings?

I suspect it’s several things. Firstly, East Anglia is largely a rural area, with only a few cities and large towns dotted around. That, and its relative isolation, helps to give it a bit of a folk horror vibe. Its flatness leads to a ‘big sky’ effect, which I think can be a bit disconcerting to visitors to the region not used to those kind of empty vistas. And the extensive marshy areas and low-lying wetlands – not to mention the curtain of the North Sea that bounds the region – means that mists and fog are not unusual – always good in a ghost story. There are also so many reminders of the past in the landscape – Norman churches, Roman remains, country houses and old parklands etc – that point to how strongly the influence of the past still resonates in the present. Then, to top it all, you have Cambridge and the sizeable number of ghost story writers who studied there during the latter part of the 19th and early 20th centuries; the region clearly had an influence on their work, as you can see in this collection.

In your book, Ghostland, you discuss your fascination with M. R. James, and visit the area around his childhood home in Suffolk. You choose two James stories in Eerie East Anglia and it must have been hard to narrow it down to that. What is it about these stories that represents James in East Anglia for you?

It was really tough to settle upon one or two M. R. James tales. But he’s such an important part of the English ghost story tradition, and such a quintessentially East Anglian character, having grown up in Suffolk and then studied and taught at Cambridge for much of his life. In the end I thought it was important to include one of the tales from his first collection, and when opting for one with an East Anglian setting it was hard not to choose “Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad”. Of course, it’s such a well-known story that I was conscious that many readers of the collection would already be familiar with it – but it seemed wrong to opt for a lesser-known tale that wasn’t as effective, just to satisfy those seeking novelty; I figured with James that I’ve never be able to offer a rarity that real aficionados weren’t already familiar with, in any case, so opted for the Burnstow exploits of Parkins. It’s a story that really resonates with me, partly because of its associations with some of those striking black-and-white visuals in Jonathan Miller’s television adaptation, and more because the setting – the Suffolk coast around Felixstowe and possibly Dunwich – is somewhere we went on family holidays when I was a teenager.

James’s influence over so many other writers in the collection is so apparent that I thought it would be fitting to break the rule I otherwise had of only having one entry per writer. For a second story I thought a less well-known tale would be good to include, and for a while I was going to opt for his only Norfolk-set tale, ‘The Experiment’. In the end though, I thought it would be apt to end the collection with the last story James wrote, ‘A Vignette’, which was published a few months after his death. It’s a wonderful tale, made all the more intriguing because its setting is the village of Great Livermere, near Bury St Edmunds, where he grew up – and it’s very tempting to think that in the story James is sharing with us a real, personal childhood experience of the eerie that he experienced. Livermere is also a strange, haunted kind of place, that’s well worth a visit – and that visit I made there was the catalyst for me to write Ghostland.

It’s hard to discuss East Anglia without mentioning the sea. The Norfolk coast has a particularly strong identity that we see in H. R. Wakefield’s ‘The Seventeenth Hole at Duncaster’ (a great story – and a new one to us) and R. H. Malden’s ‘Stivinghoe Bank’, which was inspired by the lonely vistas of Blakeney Point. Do you have a favourite coastal spot, eerie or otherwise, in East Anglia?

Well, Blakeney Point is certainly a magical and strange spot – and I describe a particularly unnerving visit that I made there one autumn in my book Ghostland. As well as ‘Stivinghoe Bank’, there’s also a story by E. F. Benson (‘A Tale of an Empty House’) that features the Point as a location, so it has an excellent spooky literary pedigree.

I’m also very fond of Wells and Holkham Woods – the strip of Corsican pine trees that covers the dunes for several miles along the middle of the north Norfolk coast. It’ll be familiar to people who have seen the 1972 BBC ‘Ghost Story for Christmas’ adaptation of A Warning to the Curious, as the place where Paxton (played by the wonderful Peter Vaughan) unearths the lost crown of East Anglia – along with its guardian, William Ager…

In the introduction to the collection you mention that East Anglia has one of the most rapidly eroding coastlines in Europe, and we certainly felt this when we visited Dunwich for the Weird Walk book, while in the Fens we saw farmland returning to marsh, with positive environmental results. Is there something about this battle with water, the reclamation and loss of land, that adds to the region’s haunted quality?

It can’t hurt it, can it! That sense of uncertainty, that we’re not in control of our fate – and that despite all of our technology and resources we can’t stop the sea from taking the land when it wants to, fits in nicely with some of the key themes of ghost stories and weird tales…

Of the more recent pieces in the book, we particularly enjoyed Daisy Johnson’s ‘Blood Rites’. There seems to be more uncanny fiction around at the moment, especially tales with a connection to landscape. Do you think there has been a resurgence in this kind of writing, or is it simply more visible currently?

Definitely. Having grown up in the Fens, I also love Daisy’s ‘Blood Rites’, as for me it really captures a brilliant sense of the place.

Uncanny writing in which the landscape and a sense of place is prevalent seems very much in the ascendancy at the moment, which is something I’m happy about. My first (and to date only!) novel, The Listeners, was also one where I wanted the landscape to play a central role. I based its setting on the tiny West Norfolk village in which my nan lived, as I loved all of its woods and local folklore when I visited as a kid in the 1980s. Even back then, I think, I was aware of the sense that it was a place that seemed somewhat anachronistic and out of time – so setting a dark, gothic novel of family secrets in an imagined 1940 version of the village seemed like a natural thing to do!

Fearful Tales of Field and Fen is such a captivating subtitle. I absolutely love this entire series. I'll be reading both books asap!